Pyramid Oceanic Erosion

The great pyramids of Khufu and Khafre have long mystified archeologists. Towering over the shorter imitations that surround them, these two marvels of engineering and human effort, colloquially known as the Giza Giants, are distinguished from the other Egyptian pyramids by their superior size and construction quality. Out of their many abnormalities, this article attempts to explain one of them. On the exterior of the Khafre pyramid, there is a striking pattern of bands that is present. What are the characteristics of these bands and what caused them to form?

The Bands

Below is an image of the Khafre pyramid from antiquity.

Three distinct bands are visible. The upper band, or “cap”, showcases the polished, albeit weathered, Tura limestone that originally encased the entirety of the structure.

The middle band is absent of the smooth Tura that once covered it. Instead, it exposes the harder Mokattam limestone backing blocks that serve as the pyramid’s core.

Finally, the lower band is the largest of the three. It appears neither like the smooth Tura limestone of the upper band, nor like the orderly Mokattam limestone blocks of the middle band. Instead, it seems like a single, solid, jagged blob of rubble. This is because the lower band consists of a uniform, cement-like detritus accretion (explained in the following section).

Lower Band Composition And Nature

From 1909 to 1910, after the above photo was taken, a German archeologist named Uvo Hölscher conducted a large-scale excavation of the lower band detritus to reveal the concealed Mokattam backing blocks beneath. His field notes, published in 1912, provide insight into the composition and characteristics of the detritus.

Khafre Pyramid — Post-Excavation

Compositionally, it was found that the lower band detritus consisted primarily of limestone (calcite; CaCO3), as well as clay, silt, sand, and gypsum and halite (sodium chloride; NaCl) salts.

Contrary to Uvo’s expectations, rather than a loose collection of debris, he found a mixture that had presumably cemented into a rock-hard formation. The hardness was greater than anticipated, oftentimes being as hard as the Mokattam backing blocks themselves. This posed significant challenges for the excavation because it required pickaxes to mine.

Despite their similar hardness, Uvo noted in his observations that this cemented mass was often so distinct from the Mokattam walls that it could be peeled away, leaving a scar on the original stone. This indicates that the lower band detritus was an accretion rather than the original monument falling apart.

Furthermore, Uvo frequently described both the detritus and the backing blocks as having been “salt-eaten” — chewed or corroded by salt. This is a phenomenon that occurs when saline water enters limestone rock through its pores, then evaporates to leave behind salt crystals. As these crystals subsequently expand, they exert outward pressure from within the limestone and cause it to experience spalling. This results in an eaten, porous look.

Given these objective characteristics, it is now time to examine some hypotheses that attempt to explain how the lower band, and the Khafre banding pattern in general, came to be. Specifically, let’s try to answer the following question: how did the Tura limestone casing of the middle and lower bands transform into a salt-rich, rock-hard limestone accretion encasing only the lower band?

Considering Human Cause

The most popular theory that attempts to explain the missing Tura, and the subsequent formation of the lower band limestone detritus, involves human cause. This theory suggests the following.

First, in 1303 AD there was a severe earthquake that may have loosened the Tura casing of the Khafre pyramid, making it easier to extract. Then, in the 14th century, the conveniently available Tura could have been mined to construct major buildings in medieval Cairo. Such an intensive quarrying process would likely have produced a large volume of limestone fragments that settled on the lower steps of the pyramid and were eventually cemented together by a fine-grained matrix of sand, silt, and salts from the occasional rainfall. This type of concretized rock formation is called a breccia and is quite geologically common.

Unfortunately, however, such a hypothesis does not adequately answer several key questions.

Firstly, what is the source of the high salt concentration in the rocks? This theory originally suggested that the salt may been latent to the limestone, but recent research has discovered the existance of a halite gradient on the Giza plateau, where rocks closer to ground level exhibit significantly higher salt content than rocks higher up (Gauri, 1984). This is characteristic of an external salt source rather than latent origination.

Secondly, why does the Tura casing of the cap remain untouched? If the Tura was scavenged by medieval builders, it seems odd that they would not take the upper Tura after having already assembled scaffolding for the rest of the excavation.

Thirdly, why is the middle band, which is visibly distinct from the lower band, free from any detritus? If the detritus was formed from remnant limestone fragments, it seems unlikely that none would settle in the middle band, or that the boundary between the lower and middle bands would be so clearly defined.

In order to arrive at a conclusion that is better aligned with Uvo’s observations and provides satisfactory answers to these outstanding questions, let’s start by examining the middle band in more detail.

Middle Band Analysis

Below is a zoomed-in shot of the upper half of the pyramid.

As previously mentioned, we can observe that the middle band is remarkably clear of its Tura or any detritus.

We can also see that the Tura casing of the cap has a boundary that is parabolic in shape on each face of the pyramid. This is further evidence against the human cause hypothesis because, to maintain gravitational efficiency, human scavengers utilizing pulley systems would have worked level-by-level from the ground up rather than excavating the Tura in such a natural curve.

Combined, these two observations give the impression of an undercut notch with a parabolic shape. Notably, this type of natural erosion pattern is a hallmark characteristic of coastal undercutting, in which ocean waves erode material from the base of a cliff or rock formation while leaving the upper portion of the structure overhanging.

This leads us to consider a second hypothesis: that the Khafre bands formed due to wave erosion. Though this theory may seem impossible at first glance, let’s examine the evidence objectively in order to determine whether it might hold merit. Specifically, let’s evaluate whether it answers our previously unanswered questions, and whether it produces detritus that matches Uvo’s descriptions.

Oceanic Erosion Hypothesis

The wave erosion hypothesis postulates that, at some point in the past, the Khafre pyramid was partially submerged under a large body of water. If this water was saline ocean water, it would explain the high concentration of salt observed on the Giza plateau, providing a plausible external salt source. It would also explain the halite gradient because, as salt water recedes, salt is deposited in greater concentrations near the base of a rock formation than near its top.

Under this hypothesis, the Tura casing of the lower and middle bands was naturally eroded by water. If the waterline stopped at the middle band and did not reach the cap, it would explain why the Tura of the cap remains intact and was not similarly eroded.

Regarding the middle band, the reason it is clear of any detritus is because vigorous wave action at the waterline would have scoured any that attempted to form. Furthermore, since this level was near the water’s surface, it would have been difficult for detritus to precipitate here due to a lack of pressure. We will learn why the presence of pressure is necessary for detritus formation later in this article.

We have now answered the questions that the human cause hypothesis leaves unexplained. However, this theory begets a new question. If the lower and middle bands of the Khafre pyramid experienced wave erosion, why was only their Tura casing stripped while the underlying Mokattam, clearly visible in the middle band, remains intact?

To understand the answer, let’s learn about the specifics of how the erosion occurred.

Erosion Mechanisms

The Tura of the lower and middle bands was completely eroded by water via two mechanisms: physical abrasion and chemical dissolution. While both Tura and Mokattam limestone are similarly affected by physical abrasion (erosion caused by fine-grained particles carried in high-velocity water), Mokattam is much more resilient against chemical dissolution, the more prominent eroding force.

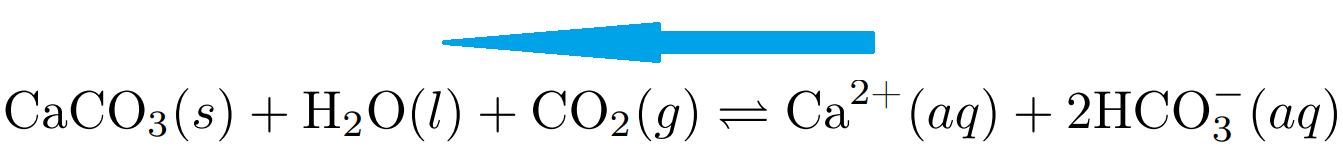

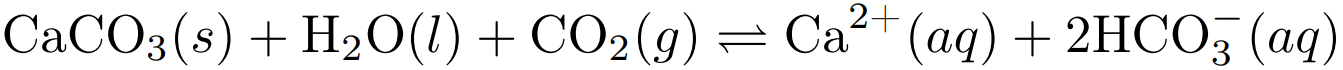

According to the chemical process of karstification, limestone is able to react with water and carbon dioxide to turn into aqueous calcium and bicarbonate ions under certain conditions. The chemical equation governing this reaction is presented below.

Karstification — Chemical Equation

Ocean water is normally supersatured with respect to these ions, so alone is not enough to allow karstification to occur. When ocean water mixes with freshwater, however, the resultant brackish water of the mixing zone becomes temporarily undersaturated and enables limestone to chemically dissolve. This was discovered by observing limestone coastlines that feature freshwater outlets.

Since the Giza plateau is positioned near the Nile river, a large source of freshwater, it is likely that brackish water was present during the period that the Khafre pyramid was submerged. Consequently, it is likely that karstification played a major role in the disappearance of the pyramid’s Tura limestone casing.

The Mokattam limestone backing blocks, on the other hand, remain intact due to their resilience against karstification. There are two factors that contribute to this resilience. Firstly, Mokattam is less pure than Tura. While Tura may be comprised of upwards of 99% calcite, Mokattam is more heterogenous, containing a high percentage of impurities such as dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) and magnesium. These impurities shield the calcite of the rock by impeding erosion pathways, which slows down the karstification process. Secondly, Mokattam is less porous than Tura. Its lower porosity prevents brackish water from permeating deeply into it and decreases reaction surface area.

Therefore, under the oceanic erosion hypothesis, the observation that the Tura is gone while the Mokattam remains is not only explainable, but expected.

Finally, let’s investigate the true identity of the lower band detritus. What is it, how did it form, and does the material expected by this theory match Uvo’s descriptions?

Detritus Formation

According to the oceanic erosion hypothesis, the lower band detritus cannot be a breccia. Since the Tura was dissolved, not excavated, there were no limestone fragments to be cemented. Instead, the detritus is likely limestone precipitate that formed from the dissolved calcium and bicarbonate ions when the water eventually, and necessarily, receded.

Water, being more dense than air, exerts pressure that is greater than that of the atmosphere and that increases with depth. As the water level of the Giza plateau fell, it is likely that the decreasing pressure in the water caused dissolved CO2 to be released in a natural process known as degassing.

Note: This is a phenomenon that is demonstrated whenever you open a soda bottle. When the cap of a fizzy drink containing dissolved CO2 is undone, the bottle experiences a decrease in pressure that causes degassing to occur. As a result, the CO2 contained in the liquid is released as fizz.

As CO2 was released, the chemical equilibrium in the water would have shifted to the left of the reversible karstification equation. In order to restore balance, this would have caused the reaction to occur in reverse and the previously dissolved limestone to precipitate as a solid.

Limestone that is formed in this way is known as Travertine limestone. It is a type of limestone that has a similar hardness to Mokattam and would have formed as a distinct accretion covering the backing stones. Since this accurately matches Uvo’s descriptions, Travertine is likely the true identity of the lower band detritus.

As further confirmation, we can look at an aerial view of the pyramid to find that there are horizontal marks visible across the lower band. These lines — relics of the Travertine’s formation — are characteristic of a receding waterline and serve as strong evidence for our precipitation theory.

Travertine Formation — Receding Water Level Lines

Conclusion

The exterior of the Khafre pyramid exhibits a mysterious banding pattern. In an effort to explain this pattern, we have examined the two leading hypotheses: human cause and oceanic erosion. Due to the human cause hypothesis being unable to explain the existance of the halite gradient, the endurance of the Tura cap, or the middle band’s freedom from detritus, we have determined it to be lacking.

Instead, we have found that the oceanic erosion hypothesis provides more adequate explanations for these observations. By learning about the processes through which limestone coastlines erode and can re-form, we were able to establish a more compelling origin for the detritus of the lower band, and the banding patterns in general.

We can therefore conclude that, at some point after the Khafre pyramid was constructed, the Giza plateau was likely temporarily submerged in a large body of oceanic water that caused the Khafre pyramid’s iconic bands to form.

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Pyramid_of_Giza

- Hölscher, U. (1912). Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Chephren [The funerary monument of King Khafre]. J.C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breccia

- Gauri, K. L., & Holdren, J. J. (1981). “Deterioration of the Stone of the Great Sphinx.” In: Newsletter of the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE), No. 114, pp. 35–47.

- Gauri, K. L. (1984). “Geologic Study of the Sphinx.” In: Newsletter of the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE), No. 127, pp. 24–44.

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0302352480800466

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karst

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Travertine